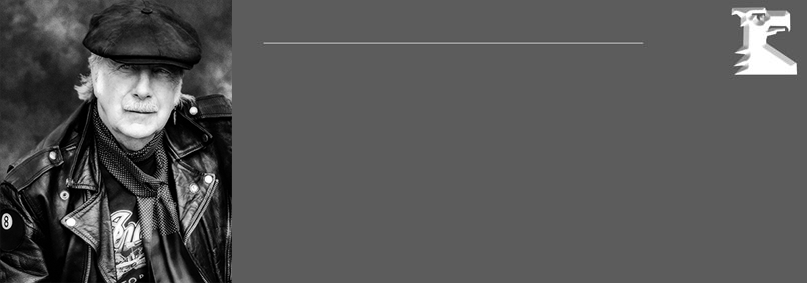

At about the age of eight, John’s life-long passion for photography was born when he spotted a plastic camera at a local funfair in London’s East End. He just had to win it, it was as simple as that. Knowing that possessing the camera would let him take home all the memories of that day.

There is always something new to appreciate about ‘ground-breaking’ professional photography. John Chillingworth wrote in his series evaluating photography’s ‘greats’, that he has seldom, if ever, met someone with the same natural creative needs as the good and great of earlier generations. Whatever the rule, John Claridge is the exception.

Another case of déja vu? An East End education (or lack of it). Left school at 15 – talked his way into his first job in photography and the rest is history!

Well, no! John Claridge is, in every way, a one-off. True, the boy from Plaistow, with a handful of ‘jack-the-lad’ cultural contemporaries could have drifted into dead-end employment, or brushes with the law, or worse, but there was something different about him.

As a consequence, in 1960, at the behest of the West Ham Labour Exchange, he dressed in his best East End ‘duds’. with hair plastered at a jaunty angle and armed only with a bucketful of determination, the boy from Plaistow went ‘up West’. The interview resulted in a job at McCann-Erickson in the Photographic Department.

He strode forward with the kind of youthful exuberance, which college-educated contemporaries often failed to comprehend, let alone emulate, Claridge grew in stature.

During the two years he worked at McCanns, not only did he have his first one-man show, he was inspired by many, namely the legendary designer Robert Brownjohn. His work, exhibited at this first one-man show, was acclaimed in the photographic press as ‘shades of Walker Evans’.

At seventeen he turned up on the doorstep of Bill Brandt’s Hampstead home – to give him one of his treasured prints. Gentle and polite, Brandt invited him in; sought the young Claridge’s opinion on his current work and sent him away feeling ten feet high.

Recommended by established photographers and art directors, he became David Montgomery’s assistant between the ages of seventeen and nineteen.

By the tender age of nineteen he had opened his own studio near London’s St Paul’s Cathedral.

His ideas and his images matured rapidly. A mix of editorial and advertising commissions brought him and his easy confidence to the attention of 1960s advertising trend-setters.

The result of which has been the presentation of over 700 awards for his work.

His by-line became familiar in many of the monthly magazines of the day and his reputation began to move from a national to an international level.

By the age of twenty-three, as well as having a home on the Essex marshes and a de rigueur E-type Jaguar, although his real sporting love was and still is the motorbike, he had written, produced and shot a short film titled “Five Soldiers”. An American Civil War tale which, when shown on a university campus in the US, caused a riot among the students as it was compared with the war in Vietnam … the press said compared the film tp Luis Buñuel. The film was eventually banned but made its way onto the underground circuit.

A doyen of the ‘golden age’. He realises now that he had been working in the ‘golden age of advertising’, and as the years melted into decades, the commissions took him around the world. Tourist boards in the Bahamas, India and the US recognised his highly individual visual talent.

Banks, whisky distillers, international corporations, car manufacturers, all were (and still are) prepared to give him his head to create images that inspired their ad agency art directors to greater and more stunning campaigns.

So, what is it that makes John Claridge great? He is a man of the world, whose influence will be transmitted to future generations of photographers.

Throughout his working decades he has maintained a mile-high wall of professionalism, which, despite today’s clients who sometimes attempt to stifle creativity, as well as the virtual absence of passion in the business, he holds true the belief that his photography is from the heart – not the head!

John’s work has moved on over recent years. Here is what eminent photography critic and historian Helena Srakocic-Kovac recently had to say about John’s work: “When you decided to pull back from advertising … which, I think, is such a shame because you revolutionised it and elevated it to an art form … you have been substituting it with work of equivalent value, guts and visual strength but so very different … so much to see … to me at times it appears as if it’s not yours … unstructured and scattered in its beauty … you used to tell stories and now it’s more about feelings and moments in life …”

His work is held in museums and private collections worldwide, including The Arts Council of Great Britain, Victoria & Albert Museum, National Portrait Gallery and The Museum of Modern Art.

He has also published five books: “South American Portfolio” (1982), “One Hundred Photographs” (1988), “Seven Days in Havana” (2000), “8 Hours” (2002), and “In Shadows I Dream” (2003).

With thanks to John Chillingworth and Helena Srakocic-Kovac, the authors and copyright holders of this text.